Ask people why they work out, and chances are glucose levels and insulin sensitivity won’t enter the conversation. But for many people, physical exercise can be a game changer for metabolic health.

Produced and released by the pancreas, insulin is a regulator in myriad metabolic processes.

“Insulin plays a number of important roles, including allowing glucose [a.k.a. blood sugar, the simplest form of carbohydrate] to turn into energy for the body to function, and signaling the liver when it’s best to store sugar for later on,” explains Dr. Rekha Kumar, chief medical officer of Found and former medical director for the American Board of Obesity Medicine.

Combined with a healthy diet and the guidance of a healthcare provider, exercise can help individuals maintain normal blood sugar levels and reduce the risk of related health issues. If you want to learn how to increase insulin sensitivity through exercise, read on.

What Does Insulin Do?

Simply stated, insulin directs the flow of sugar from the blood into cells. When your metabolism is functioning properly, the order of operations goes like this:

- You ingest food

- That food is broken down by the digestive system into glucose

- That glucose is then released into your bloodstream

- Your pancreas, now detecting elevated blood sugar, secretes the hormone insulin

- That insulin helps shuttle the glucose into cells for conversion into fuel.

Glucose is consequently cleared from the bloodstream with any unused sugar stored as glycogen in the liver and muscle tissue and converted into fat in adipose tissues for later use (say, the final mile of a 10k or when it’s been hours since you last ate). Blood sugar levels are now back to normal.

“[Insulin’s] ability to regulate blood sugar is critical, and when it doesn’t function properly, it can lead to many health issues like type 2 diabetes. When the body doesn’t make enough insulin, we see other health problems such as type 1 diabetes,” Kumar says.

What Is Insulin Sensitivity?

Insulin sensitivity refers to how receptive your body is to insulin. “Having a good sensitivity to insulin means that your muscles and fat only require a certain dose of insulin to turn carbohydrates into energy,” Kumar says.

However, if you have decreased insulin sensitivity, your need for insulin is higher than normal, requiring your pancreas to produce more of it to police your blood glucose levels. Over time, the strain of producing so much insulin can take a toll on the pancreas, which may eventually stop working altogether. This is the pathway to prediabetes and type 2 diabetes.

Insulin sensitivity vs insulin resistance

Whereas insulin sensitivity is a reference to the body’s response to insulin without regard to whether it’s normal, high, or low, insulin resistance is a state of significantly impaired or decreased insulin sensitivity.

“Insulin resistance happens when your cells stop responding to insulin, which can lead to higher insulin levels and blood sugar levels, initially, and more concerning effects down the line, including type 2 diabetes,” Kumar says.

She explains that insulin sensitivity can be strictly measured by a procedure called the clamp study, which requires an intravenous glucose infusion. However, it is more commonly determined by metrics like fasting blood sugar levels, fasting insulin levels, and oral glucose tolerance tests.

The Relationship Between Exercise and Insulin Sensitivity

Sedentary living, among its other perils, can be problematic for blood sugar. But exercise can help improve insulin action in several ways.

1. Insulin is activated by… physical activity

The demand for energy made by muscles during intense exercise triggers insulin to steer glucose into cells as fuel.

“So instead of that glucose just circulating in the blood, it ends up going in the muscle,” says Todd Buckingham, Ph.D., triathlete, coach, and professor of movement science at Grand Valley State University in Allendale, Michigan.

But, he explains, increased uptake by skeletal muscle is temporary. So, exercise needs to be regular to have long-term effects. Exercise intensity also plays a role.

According to an article published in BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, performing 30 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise three to five times per week is associated with improved insulin sensitivity. And incorporating small amounts of high-intensity training may, in some cases, produce even greater benefits.

2. Weight loss promotes insulin sensitivity

Regular exercise can also reduce adiposity (body fat), which has been shown to improve the insulin response. A 2017 study compared four groups of women classified exclusively according to weight status and weight loss history.

Researchers found that those who had successfully maintained meaningful weight loss (15% of bodyweight) for at least one year were significantly more sensitive to insulin than the other groups.

3. Muscle gobbles glucose

Building skeletal muscle via resistance training can also have a positive effect. A cross-sectional study of nearly 5,000 subjects found a positive relationship between muscle mass and insulin sensitivity.

“If you have more muscle mass, you have more tissue that needs glucose, so you can increase glucose uptake to the muscle,” Buckingham says. “Doing both cardio and resistance training is going to be better than just doing either on its own.”

4. Exercise curbs cortisol

Stress triggers the release of the hormone cortisol, which subsequently triggers the release of blood sugar to power the body’s response to that stress. As a result, chronic, or ongoing, stress can eventually lead to reduced insulin sensitivity.

But there may be no better antidote for stress than regular exercise. While exercising itself places the body under momentary stress, physical activity reduces it during the time between workouts, thereby reducing overall cortisol and, by extension, the impact of stress on blood sugar.

What’s the Best Exercise for Insulin Sensitivity?

So, which type of exercise training is best for improving insulin sensitivity? Steady-state (a.k.a. “zone 2”) cardio? High-intensity interval training (HIIT)? Weightlifting?

“All of the above are correct,” Kumar says. Because exercise increases glucose uptake from the blood, any form of physical activity can be beneficial. However, there are some differentiating factors worth considering.

Aerobic exercise

Also known as “cardio,” “steady-state,” or “zone 2 cardio,” aerobic exercise is any activity that elevates your heart rate above a normal resting level. Walking, jogging, swimming, and cycling are common examples.

During aerobic exercise, the body uses oxygen to help create energy and releases carbon dioxide at a faster rate, which is why you typically breathe more rapidly. (As opposed to being completely breathless during an anaerobic workout, which would indicate you’re in high-intensity territory.)

Most people are familiar with some form of aerobic exercise and may, for example, find daily walks in their neighborhood more approachable than jumping into a HIIT class or experimenting with resistance training.

The best workout is the one you’ll actually do. So if cardiovascular exercise is appealing, stick with aerobic workouts.

HIIT

High-intensity interval training workouts typically consist of short periods of intense effort, during which you should feel breathless, interspersed with periods of rest. If you’ve done a workout that adheres to a Tabata (20 seconds of work followed by 10 seconds of rest for eight rounds), AMRAP (as many reps or rounds as possible), or EMOM (every minute on the minute) format, you’ve done HIIT.

As noted above, there’s some evidence that higher-intensity activity may be more effective at helping insulin sensitivity than moderate-intensity exercise. And some research shows that a higher volume of HIIT (e.g., a 40-minute workout vs. a 25-minute workout) may yield even better results.

However, HIIT may not be appropriate for everyone, including those new to exercise. If you do decide to try HIIT, be sure to incorporate rest days and lower-intensity workouts into your programming as well, as too much HIIT can lead to overtraining.

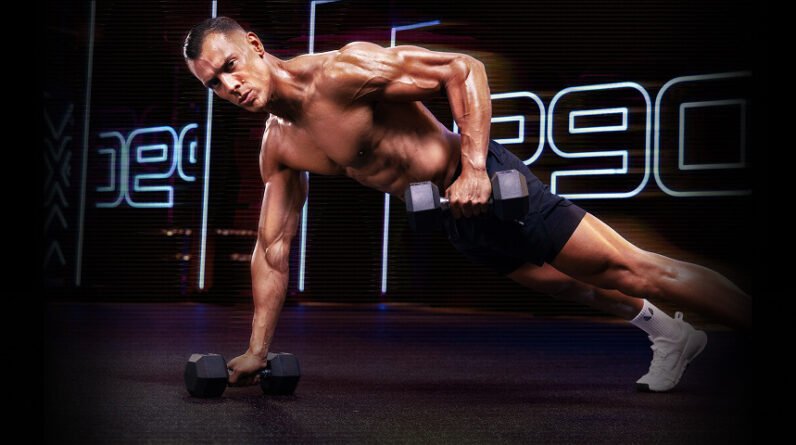

Resistance training

Like aerobic exercise, resistance, or strength, training improves insulin sensitivity by increasing the uptake of glucose from the bloodstream to fuel the muscles during (and beyond) a given workout.

Buckingham recommends focusing on compound lifts that engage large muscle groups. “Squats, bench press, and back exercises like the row all use really large muscle groups,” he says. “We want to focus on the large muscles because the more muscle mass that we have the better the glucose uptake is going to be.”

Additionally, there’s some evidence that focusing on individual muscles when lifting (e.g. doing a single-leg calf raise or single-arm biceps curl) may reduce insulin sensitivity in the other muscles of the body.

Yoga

Yoga and other low-impact workouts that combine breathing, mobility, stretching, and meditation may also help improve insulin sensitivity. One study found that individuals with type 2 diabetes who were enrolled in an integrated yoga therapy program for 120 days showed significant improvements in glycemic control, insulin sensitivity, and other key biochemical parameters than the control group, which did not incorporate yoga into their treatment.

Bottom line: Any form of physical activity can help with insulin sensitivity, but exercise alone is not a silver bullet. “It’s a combined effort. A mix of effective tactics like eating a low-carb diet, incorporating periods of fasting, and focusing on strength training to build muscle is recommended,” Kumar says.

So before you start, make sure you work with your healthcare provider to develop a holistic plan that’s tailored to your individual needs.